CT’s state flower, the mountain laurel, is at peak bloom in some areas; where to see it

CT Insider – Heather Zidack and other professionals discuss Connecticut’s State Flower, the Mountain Laurel and where to see it in bloom this spring.

Web cookies (also called HTTP cookies, browser cookies, or simply cookies) are small pieces of data that websites store on your device (computer, phone, etc.) through your web browser. They are used to remember information about you and your interactions with the site.

Session Management:

Keeping you logged in

Remembering items in a shopping cart

Saving language or theme preferences

Personalization:

Tailoring content or ads based on your previous activity

Tracking & Analytics:

Monitoring browsing behavior for analytics or marketing purposes

Session Cookies:

Temporary; deleted when you close your browser

Used for things like keeping you logged in during a single session

Persistent Cookies:

Stored on your device until they expire or are manually deleted

Used for remembering login credentials, settings, etc.

First-Party Cookies:

Set by the website you're visiting directly

Third-Party Cookies:

Set by other domains (usually advertisers) embedded in the website

Commonly used for tracking across multiple sites

Authentication cookies are a special type of web cookie used to identify and verify a user after they log in to a website or web application.

Once you log in to a site, the server creates an authentication cookie and sends it to your browser. This cookie:

Proves to the website that you're logged in

Prevents you from having to log in again on every page you visit

Can persist across sessions if you select "Remember me"

Typically, it contains:

A unique session ID (not your actual password)

Optional metadata (e.g., expiration time, security flags)

Analytics cookies are cookies used to collect data about how visitors interact with a website. Their primary purpose is to help website owners understand and improve user experience by analyzing things like:

How users navigate the site

Which pages are most/least visited

How long users stay on each page

What device, browser, or location the user is from

Some examples of data analytics cookies may collect:

Page views and time spent on pages

Click paths (how users move from page to page)

Bounce rate (users who leave without interacting)

User demographics (location, language, device)

Referring websites (how users arrived at the site)

Here’s how you can disable cookies in common browsers:

Open Chrome and click the three vertical dots in the top-right corner.

Go to Settings > Privacy and security > Cookies and other site data.

Choose your preferred option:

Block all cookies (not recommended, can break most websites).

Block third-party cookies (can block ads and tracking cookies).

Open Firefox and click the three horizontal lines in the top-right corner.

Go to Settings > Privacy & Security.

Under the Enhanced Tracking Protection section, choose Strict to block most cookies or Custom to manually choose which cookies to block.

Open Safari and click Safari in the top-left corner of the screen.

Go to Preferences > Privacy.

Check Block all cookies to stop all cookies, or select options to block third-party cookies.

Open Edge and click the three horizontal dots in the top-right corner.

Go to Settings > Privacy, search, and services > Cookies and site permissions.

Select your cookie settings from there, including blocking all cookies or blocking third-party cookies.

For Safari on iOS: Go to Settings > Safari > Privacy & Security > Block All Cookies.

For Chrome on Android: Open the app, tap the three dots, go to Settings > Privacy and security > Cookies.

Disabling cookies can make your online experience more difficult. Some websites may not load properly, or you may be logged out frequently. Also, certain features may not work as expected.

CT’s state flower, the mountain laurel, is at peak bloom in some areas; where to see it

CT Insider – Heather Zidack and other professionals discuss Connecticut’s State Flower, the Mountain Laurel and where to see it in bloom this spring.

By Pamm Cooper, UConn Home & Garden Education Center This spring has been a dramatic one as ornamental trees and shrubs are putting on quite a colorful floral display. Many deciduous ornamentals including redbuds, forsythia, crabapples, fruit trees, quince azaleas and many others were not adversely affected by last summer’s drought and the cold, windy winter and frozen soils that followed. A lesser noticed but significant drama is the negative effect these same environmental conditions had on ornamental and native evergreens.

Rhododendrons and ‘Green Giant’ arborvitae seemed to suffer the most damage followed by cherry laurels and hollies. Last year’s drought conditions that extended into late fall combined with very windy winter conditions and frozen soils were tough for some evergreens. Winter desiccation injury on broadleaved and needled evergreens causes foliage browning when plants cannot take up the water needed to keep foliage healthy. Damage to many rhododendrons and some azaleas could be seen during the winter and is still evident this spring. Buds may provide new leaves by June if branches are still alive.

In contrast, 'Green Giant’ arborvitaes suddenly showed symptoms after warm weather began this spring. This was evident especially in trees on windy sites. Needles are brown or off color and time will tell if they are able to recover. If branch tips are flexible and show new buds, growth may resume. Prune any dead branches that show no signs of recovery.

Eastern tent caterpillars have hatched from overwintering egg masses on native black cherries. Silken nests are evident located in crotches of these trees. Caterpillars feed outside the tents at night and hide in them during the day. There is only one generation, and feeding is generally finished by late June. Trees have time to leaf out again to remain healthy during the growing season. Birds like cuckoos and vireos will rip tents apart to feed on the caterpillars.

If you have Oriental lilies, be alert for the lily leaf beetle. This bright red insect can severely defoliate these lilies. Adults overwinter in soil close to the plants they were feeding on the previous season. They appear as soon as lilies begin new growth above the ground. Leaf undersides should be checked for eggs and larvae and crushed when found. Leaves can be treated if needed with a product that larvae will ingest as they feed on the treated leaves. Never spray flowers with any insect control product and always follow directions as written on the product label.

Snowball aphid feeding damage is noticeable on the new leaves of European cranberry bush and snowball viburnums. As the aphids feed on the new leaves and twigs, leaves curl and twigs twist in response to aphid feeding on the sap. Aphids can be found by uncurling the leaves. Treatment is difficult as they are not out in the open where contact control products can reach them. Feeding should end within two months of egg hatch. These aphids overwinter as eggs laid on the branches of host viburnums.

Viburnum leaf beetles, Pyrrhalta viburni, are another significant pest of ornamental and native viburnums. They’re active soon after viburnums leaf out. Damage will be seen as larval populations grow and they skeletonize leaves. Some viburnums may suffer complete defoliation. This pest prefers arrowwood, European cranberry bush or American cranberry bush viburnums. Try switching to resistant varieties such as V. plicatum and Korean spicebush viburnum V. calesii if leaf beetles are a chronic pest.

If anyone has small St John’s wort shrubs or certain weigela cultivars that seem to be dead, wait and see if new growth resumes as it gets warmer and sunnier. The smaller St. Johns’ wort shrubs die back in fall, leaving brown stems with withered fruit. Prune these back almost to the ground as basal growth appears. Some weigela cultivars are just slowly getting started, while others are already full of leaves. Do not give up these plants but wait and see what happens in May.

As always, our UConn Home and Garden Education Center office staff welcomes any questions gardeners may have concerning landscape and garden plants problems. Across the New England region, people are having much the same problems as we are having in Connecticut from the winter weather, but we can hope that plant recovery be swift and complete. Enjoy the growing season and stay alert- scout for pests and other problems before they get out of hand.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at cahnr.uconn.edu/extension/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant May 10, 2025

By Marie Woodward, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

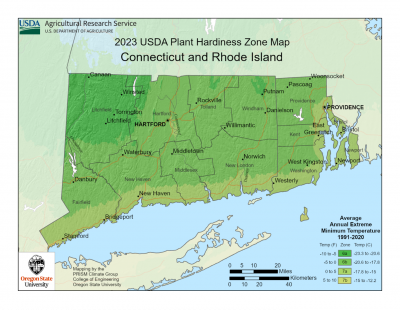

If you are wondering whether that shrub, flower, or tree that you saw in a magazine or catalog will grow well in your garden, using a hardiness zone map is your best bet to ensure success.

A hardiness zone map is a tool that divides a geographical area into distinct zones based on average annual minimum winter temperatures. These maps are used by gardeners and farmers around the world to determine which plants are most likely to thrive in a particular region. Each country has its own hardiness map that correlates to their climate. In the United States, the USDA publishes a hardiness zone map, which covers all fifty states and includes Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. It uses climate data collected over many years from weather stations throughout a specific region. Then the data is analyzed to determine average minimum winter temperatures from different areas.

The concept of hardiness zones was first introduced in 1927 by Dr. Alfred Rehder. Rehder worked at Harvard's Arnold Arboretum as a botanical taxonomist. He wanted to address the challenges gardeners and growers faced in selecting plants suited to their local climate. Prior to Rehder’s map, there was no standardized system for categorizing plants based on their ability to survive winter temperatures. His hand-drawn map featured eight hardiness zones and was based on the lowest winter temperatures recorded in various regions across the country. Rehder aimed to provide a practical tool for gardeners and growers. His map made it easier for them to choose plants with the best chances of survival in their region, ultimately contributing to more successful gardens and agricultural endeavors. Rehder’s innovative approach recognized the importance of adapting agricultural practices to local climates. In the 1960s, the USDA adopted and adapted Rehder's concept, creating the first official USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map.

Since its initial release, the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map has been updated several times to reflect changes in climate and the availability of more accurate data. The latest update of the USDA hardiness map was released in November 2023, jointly developed by the USDA's Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Oregon State University's PRISM Climate Group. This update incorporates data from 1991 to 2020, covering a broader range of weather stations than previous versions. One of the key findings from this update is that the contiguous United States has become approximately 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer on average compared to the previous map. As a result, around half of the country has shifted into the next warmer half zone, while the other half has remained unchanged. The updated map still consists of 13 zones, but now offers more detailed information on temperature ranges within each zone, including 10-degree zones and 5-degree half zones. Connecticut has two hardiness zones each of which is divided into half zones; (6a,6b); (7a,7b), to better reflect the temperatures in the state over the past few decades.

The importance of hardiness zones lies in their ability to help gardeners and farmers choose plants that will thrive in their specific region. By selecting plants appropriate for their zone, growers can reduce the risk of frost damage and increase their chances of a successful growing season. However, due to unexpected temperatures outside the average range, there is no guarantee that a plant won’t suffer but it does reduce the risk of plant damage. In addition to gardeners, researchers use hardiness zones to study the spread of insects and exotic weeds, while the USDA Risk Management Agency uses the map to help determine crop insurance rates for commercial growers.

While the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is an invaluable tool, it is important to note that it is not the only factor gardeners and farmers should consider when selecting plants. Other factors, such as soil type, precipitation, and local microclimates, can also impact plant growth and survival. Gardeners should use the map as a starting point and supplement it with local knowledge and research to make the best plant selections for their specific needs.

The development of the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is a testament to the importance of adapting agricultural practices to local climates. Since its inception nearly a century ago, the map has evolved to reflect changes in climate and incorporate more accurate data. Today, the map remains an essential resource for gardeners and researchers alike, helping them to better understand and navigate the complexities of plant growth in the diverse regions of the United States. Knowing a plant’s hardiness zone when selecting that shrub, tree or flower will help you grow the garden of your dreams.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at cahnr.uconn.edu/extension/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant May 3 2025

We Asked Arborists When to Prune Dogwood Trees, and They All Said the Same Thing

The Spruce – Heather Zidack and other professionals give their insight on pruning Dogwood Trees

By Nick Goltz, DPM, UConn Home & Garden Education Center, UConn Plant Diagnostic Lab

Using low-heat LED lights is a great way to reduce fire risk while keeping things festive. The stewards of this tree toko the extra step of installing a rope fence to discourage visitors from damaging the tree or lights. (Photo taken by Nick Goltz)

With the holidays upon us, many of us are focusing, with good reason, on last-minute gifts, travelling, reconnecting with loved ones, and all the joy and stress that will inevitably come with it. With all the hustle and bustle of the season, it can be easy to overlook some of the safety hazards that also come about this time each year, especially those involving the holiday plants that we rarely give a second thought.

On countless desks, coffee tables, and, in warmer climes, doorsteps, you are likely to encounter at least a dozen poinsettias this December. Poinsettias (Euphorbia pulcherrima) are some of the most conspicuous and popular plants associated with the holiday season here in the US. They are often thought to be highly poisonous if ingested. While ingestion may cause some mouth and skin irritation and gastrointestinal upset, sometimes with some associated vomiting or diarrhea in small animals, poinsettias are vastly “overhyped” with their supposed toxicity.

There is no documented case of human fatality associated with poinsettia ingestion, and most calls to poison control lines for ingestion report no adverse symptoms whatsoever. Medical intervention is usually unnecessary for people or pets that ingest the plant, except for those with allergic reactions to related plants (particularly those with latex sensitivity). For more information on poinsettias and their fascinating history, see Heather Zidack’s column from mid-November, “Poinsettias: The Story of a Holiday Treasure”. While poinsettias may be overblown with regard to their supposed toxicity, other common plants one might see around the holidays, including amaryllis and mistletoe, are quite toxic to humans and pets if ingested.

What we call “amaryllis” in most stores and garden centers is likely not the true South African amaryllis (Amaryllis belladonna), but rather a related South American plant in the genus Hippeastrum, which has been cultivated more extensively and has a greater number of cultivars on the market. Both are bulbous tropical plants that bloom in winter in the northern hemisphere, and both are poisonous if ingested. The bulb, commonly sold waxed or bare in stores around the holidays to be used as a table centerpiece or hostess gift, is especially toxic and should be kept away from pets and children. If you’re curious to learn more about the history and cultivation of this holiday plant, check out Dr. Matt Lisy’s recent blog post, “Amazing Amaryllis” on the UConn Home & Garden Center’s very own Ladybug Blog (https://uconnladybug.wordpress.com/).

Though in antiquity it represented fertility and offered protection from evil, mistletoe (usually Viscum album, European mistletoe and Phoradendron leucarpum, American mistletoe) has been associated with Christmas since some point in the late 1700’s. Though lovers may steal a kiss or two beneath the mistletoe this Christmas, be sure the mistletoe can’t be stolen by children or pets as you decorate for your holiday party! Although European mistletoe is more toxic than American mistletoe, both plants are dangerous if ingested, particularly by pets and children, who may be attracted to the small white berries that have a high concentration of toxin. If you know someone that accidentally ingests a plant not known to be edible, be sure to contact the poison control hotline by calling 1-800-222-1222 or by visiting https://www.poison.org. For pets, contact the ASPCA poison control hotline by calling 1-888-426-4435 or by visiting https://www.aspca.org/pet-care/animal-poison-control. Conveniently, they have a poisonous plants list on this site that you can reference as you shop at your local nursery or garden center.

Though thankfully Christmas trees (typically fir, pine, or spruce) are not known to be toxic to pets if ingested, the sharp needles can cause injury if ingested and the trees themselves can pose other hazards if not maintained with care! If you have a pet that likes to chew through wires (there is a scene in a famous Christmas movie that likely comes to mind), be sure to keep those out of reach, or perhaps opt for battery-powered illuminating ornaments. For their safety and yours, cats and birds should always be discouraged from climbing or flying into your tree!

Finally, though we all can appreciate rustic and vintage holiday décor, another strategy to reduce the risk of fire this holiday season is to upgrade your string lights to low-heat LEDs. Whatever type of string light you use, unplug it before you go to bed to help reduce fire risk. If you use a live tree, be sure to keep it watered as dehydrated trees are more likely to catch fire.

With these tips in mind, the Plant and Soil Health team at UConn wishes you and your loved ones a safe, joyous, and restorative holiday season! For questions regarding winter plant safety or for any other gardening questions throughout the year, contact the UConn Home & Garden Education Center for free advice by calling (877) 486-6271, toll-free, visit our web site at www.homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu/, or contact your local Cooperative Extension Center.

By Nick Goltz, DPM, UConn Home & Garden Education Center, Plant Diagnostic Lab

The autumnal equinox, one of two times of the year at which day and night are equal in length, just passed on Sunday the 22nd. While this point marks the astrological start of fall, many of the trees lining the roads on my drive to work (and in many of our clients’ yards) seem to want to get a head start on the season. Since late August, we’ve been getting calls from folks across Connecticut asking why the leaves on their trees are changing color and falling early. You may even be thinking, “Hey, a few of my trees are dropping their leaves early too. Is that something that can indicate how healthy they are?” In a word, maybe!

First, let me share the good news that, for most trees, premature color change and leaf drop doesn’t mean that they are in any immediate danger. Plants, much like humans and other animals, respond to stress differently depending on their environment and the kind of year they’ve been having. Just like we might see a little hair loss after a particularly stressful few months, trees may drop their leaves early as a response to stress. Identifying what is causing the stress however, is important when deciding if concern is warranted.

What type of stressors might be causing this early color change and leaf drop? For most trees, the answer is water. Connecticut and several other states in New England had a series of heavy rain events and flash flooding throughout the summer. While we’ve had hardly any rain in the land of steady habits for several weeks now, for many trees, the damage has already been done and symptoms are just appearing now. Saturated soils deprived plant roots of oxygen, damaging them and making them more susceptible to disease. Plants in especially low-lying areas, caught in floodwaters, or grown in poorly-draining clay soils likely experienced the most damage and earliest leaf drop. Some plants may have even perished outright from the damage. Besides water, excessive heat and the increased prevalence of fungal and bacterial diseases, as well as some insect pests, may have also contributed to the stress our plants are letting us know about now.

So, how can you know if the early color change or leaf drop is an issue for your favorite tree or just its way of complaining about a stressful summer? When and where the leaf change and drop is occurring can help you determine if the damage is likely a normal stress response or due to something more sinister.

Consider when the color change and leaf drop first began. In this instance, seeing some leaves begin to change in the last week of August is less concerning than seeing them change at the end of June. Plants that have their leaves change color and drop in midsummer or earlier are most likely dealing with a disease or pest issue, rather than a stress response. I recommend you get advice for these plants by contacting the UConn Home & Garden Education Center and remove them from your garden if they are unlikely to recover.

Also, consider what part(s) of the canopy was affected. Conifers such as white pine drop their leaves (we usually call them needles) in response to stress too, but you will typically see this take place on the interior of the plant – the older needles that aren’t capturing much sun anymore. Branches on deciduous trees, such as oak, that are in shady spots tend to drop their leaves early too, and this is normal.

Branches in full sun that lose their leaves very early, while others on the tree remain fine, are a bit suspicious. Mark these branches with tape or string and monitor them carefully as the plant produces its first leaves or flowers in the spring. If these marked branches do not produce leaves or flowers with the rest of the tree, get advice (again, by contacting the folks at the UConn HGEC)! The best option is usually to cut them close to the main trunk, then disinfect your pruning tools.

If you’re concerned about the health of your tree, including as a result of a potential disease or pest issue, practice good fall habits to give your trees the best foot forward next spring! Clean as much leaf litter as possible and remove it from the base of trees that dropped their leaves early. If you suspect the plant is diseased or has pests, throw away these leaves or burn them before composting. For example, many plant pathogenic fungi can survive the winter on fallen leaves and reinfect healthy plant tissue the following spring. It’s also a good idea to minimize added stress for your plants. Try not to expose them to herbicides, deicing salts, fertilizers, or other chemicals until they’re looking strong again.

If you aren’t sure how to proceed with your fall cleanup or if you’d simply like a second opinion on your favorite tree, get free horticultural consultation from the UConn Home & Garden Education Center by emailing ladybug@uconn.edu or by calling (877) 486-6271.