HGEC Newspaper Articles

The UConn Home & Garden Center's horticultural consultants and affiliate staff write a weekly column that is submitted to The Chronicle, The Hartford Courant, and other local news outlets. Read our previous articles below.

2026

A Spider Everyone Can Love

By Dr. Matthew Lisy, UConn Adjunct Faculty

Spiders are one of those creatures that humans fear. Most here in the Northeast are totally harmless, yet many times people run and occasionally hurt themselves trying to get away from them. As such, it is interesting to me that one of our most beloved plants is called “Spider Plant.” Its growth does superficially resemble a spider, but this one brings joy to its owners. In fact, it is one of the hardiest of all our houseplants.

Scientifically it is known as Chlorophytum comosum, and there is quite a bit of controversy in the scientific community over species. In the pictures accompanying this article, the differences in the leaves can be clearly seen. The great debate stems from (pun intended) differences in leaf shape. Scientists cannot decide on whether those differences represent phenotypic variation (changes in shape found within a population) or differences between species. And while it seems like this should be an easy task, look at all the differences seen in dogs, which are all the same species. While the leaves on our houseplants most likely represent different artificially selected cultivars (varieties), determining how many there are in the wild is difficult. Plants normally have some ability to change the shape of their leaves. For example, plants grown in shade tend to have larger leaves than those grown in full sun. These plants are native to South Africa, and tend to grown in forests, which could explain why such variation is seen in the wild. There were two other species listed for a while, but then those got lumped back in to C. comosum and their differences chalked up to environmental variation.

In reality, how many species there are does not really matter for us keeping these wonderful houseplants. What does matter is their forgiving nature. They grow and thrive in any typical houseplant soil. It is best to let the surface dry before watering again. They have an interesting root system that is part of the key to their success. The thick, tuberous roots store water, and that is why they can survive for much longer than other houseplants. When repotting, it is amazing how they fill the pot completely with roots. Although it sounds like this might become a problem, the Spider Plant does not mind. It responds with more leaves, and even babies.

The Spider Plant is easily propagated by planting the little plantlets that form along runners sent out by the mother plant. Simply plant these in typical houseplant soil, water well, and they will start to grow. As they do not have a fully developed root system yet, care must be taken to not let them dry out during the beginning stages. This plant is probably the most easily propagated houseplant. I still have one propagated by my first-grade teacher. It grew in the classroom when I was there, and two years later when my sister had the same teacher, it had produced babies that were sent home with each student. Despite all of life’s ups and downs, the plant is still going and thriving almost half a century later.

There are a number of interesting varieties of this plant. The leaves can be narrow, wide, or curled. The colors of the leaves are interesting as well, and can be found in any combination of leaf-types. There are green leaves with a white center stripe. Alternatively, there are green leaves with white edges. As one would expect, there are all green leaves too. Although I do not have one yet, there is a variety called ‘Hawaiian’ that has a green leaf with a yellow center. Don’t be fooled by some so-called Spider Plants that are purple – those are actually Tradescantia, or Spiderworts, which are a totally different species of plant native to the Americas. No matter which variety is chosen, with proper care Spider Plants could bring the owner enjoyment for a lifetime!

The UConn Home Garden Education Office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant February 1, 2026

Beech Bark Disease – One More Problem For Connecticut Beech Trees

By Pamm Cooper UConn Home Garden Education Office

American beeches have been suffering from beech leaf disease that is widespread in both Connecticut landscapes and forests. The prognosis for this disease is currently uncertain, but research is investigating treatments and other methods for possible control. This disease is evident from dark bands appearing on the leaves, so homeowners can to some extent seek help from licensed arborists once this symptom is evident.

Meanwhile, beech bark disease is also becoming a major threat to American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in eastern North America. This disease is a result of an interaction between a scale insect and one of two Nectria fungal pathogens. When these scales are present, beech bark disease has an increased chance of infecting the tree. The scale responsible was introduced from Europe and first appeared in Nova Scotia around 1890, according to researchers. Within forty years, the fungal pathogen combined with heavy infestations of the beech scale were killing trees, although only in Eastern Canada and Maine.

The scale insect, Cryptococcus fagisuga, will attack American beech, European beech (Fagus sylvatica) as well as Chinese and Oriental beeches, F. enleriana and F. orientalis, respectively. The scale insects pierce through the thin bark of the beeches with a stylet and inject enzymes to help digest the plant material. These small wounds in the tree can now be the entry point of fungal pathogens, including the two native Nectria spp. that can cause beech bark disease.

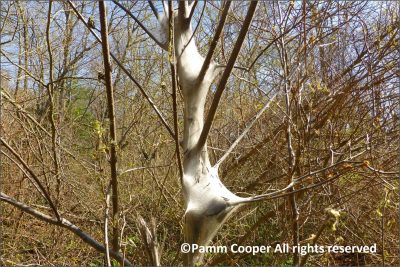

Adults mate and females lay eggs in mid- summer. Eggs hatch from late summer until early winter and form a waxy white covering. These scale insects often go unnoticed until they develop a “woolly” appearance which is evident in the winter. The immature scales overwinter on the tree, and the next year will become adults. If you notice white woolly scale insects on beeches, especially on trunks, these are likely the beech bark scale. In two to three years, scale populations can reach high levels where the trunks may appear white. Scales do not have wings, but they can be blown by the wind to new trees or transported by birds or even humans.

Disease symptoms take several years to develop after scales appear. Anyone hiking through the forests of Connecticut has probably noticed disfigured bark caused by the Nectria pathogens responsible for beech bark disease. In severely infected trees, living tissue just beneath the outer bark is killed. Cankers appear looking like rough, raised, circular disks. Fungal fruiting bodies appear in the center of these raised circles. Sometimes there are so many red fruiting bodies of the fungus that large areas of the trunk appear red. Over time, bark may crack and split off. Trunks of weakened trees can snap in high wind events. Nectria kills areas of woody tissue, sometimes creating cankers on the tree stem and large branches which in turn weaken the tree. Infected trees can thus be susceptible to other diseases and insects.

So, this is not a happy tale, but homeowners do have some good news. Controlling the scale on any ornamental or native beeches on a property resulting in the absence of these scale insects will prevent beech bark disease. Because beech can form thick stands, thin some smaller trees out so the remaining trees will retain vigor. Make sure trees that have no scale present, and no disfigured bark are left with good space between them.

In case you may need an arborist, the Connecticut Tree Protective Association has licensed arborists that can help you assess the situation with your trees. A licensed arborist will be the best choice in any case. They will be educated in tree insect and disease problems and their solutions, if any are available. Contact the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Forestry and Horticulture department for the latest news and control options for disease and insect problems. Hopefully, your beech trees will never have problems.

The UConn Home Garden Education Office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant January 25, 2026

Camellias for Color, Inside and Out

By Dawn Pettinelli, UConn Home Garden Education Office

Now that the holidays are over, the decorations are put away and scenes of dreary, wintry weather dance in our heads, one plant with flowers resembling roses that comes into bloom this time of year are camellias. These Asian natives have been cultivated for possibly 5000 years. Most of us are familiar with Camellia sinensis var. sinensis aka, tea! Black tea, white tea, green tea all come from the same plant just processed differently.

Other camellia species were noted and grown for their flowers gracing gardens of temples and nobility. Prized plants were selected and crossed and eventually made their way to England, sometime in the 1730s. These elegant and highly treasured plants soon were spread all over Europe with hybridists and propagators in Italy, France, Belgium, Holland, Portugal, Spain, Germany and the U.K. by the middle of the 19th century. More and more hybrids and cultivars were being developed with the number now well over 3,000. As their popularity grew, camellias were soon being grown in Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. Societies, like the American Camellia Society sprang up and shows were held (and still are) to exhibit various forms and compete for awards.

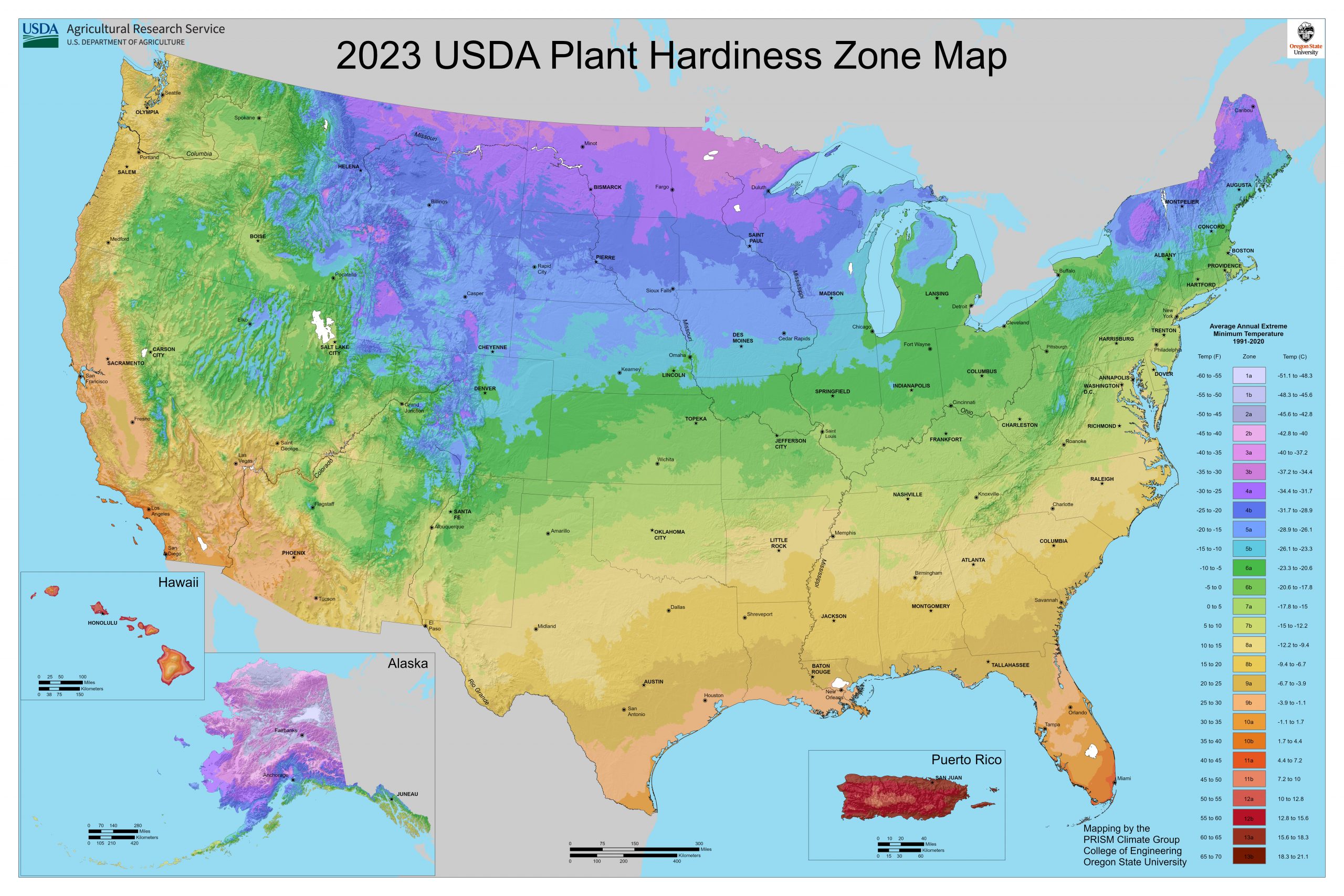

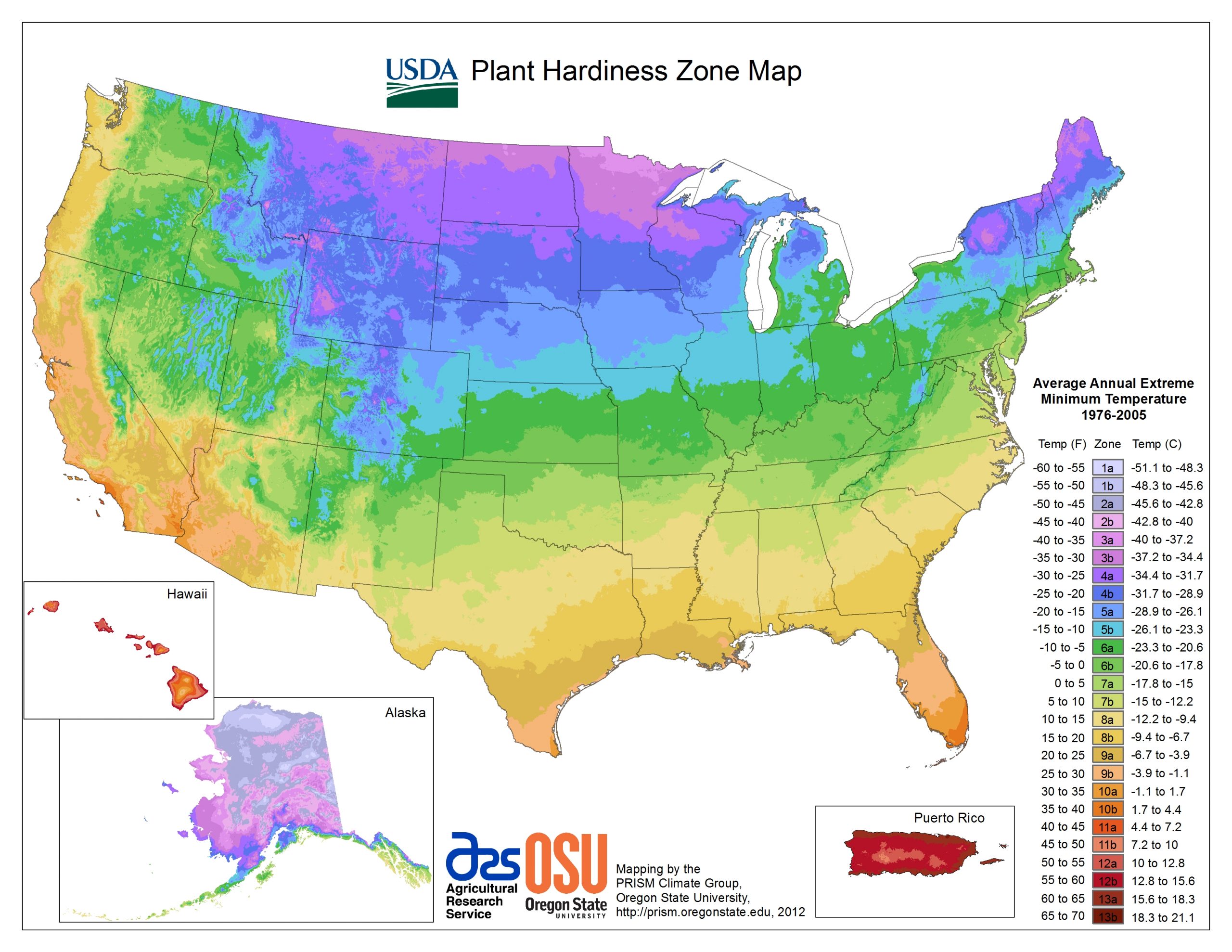

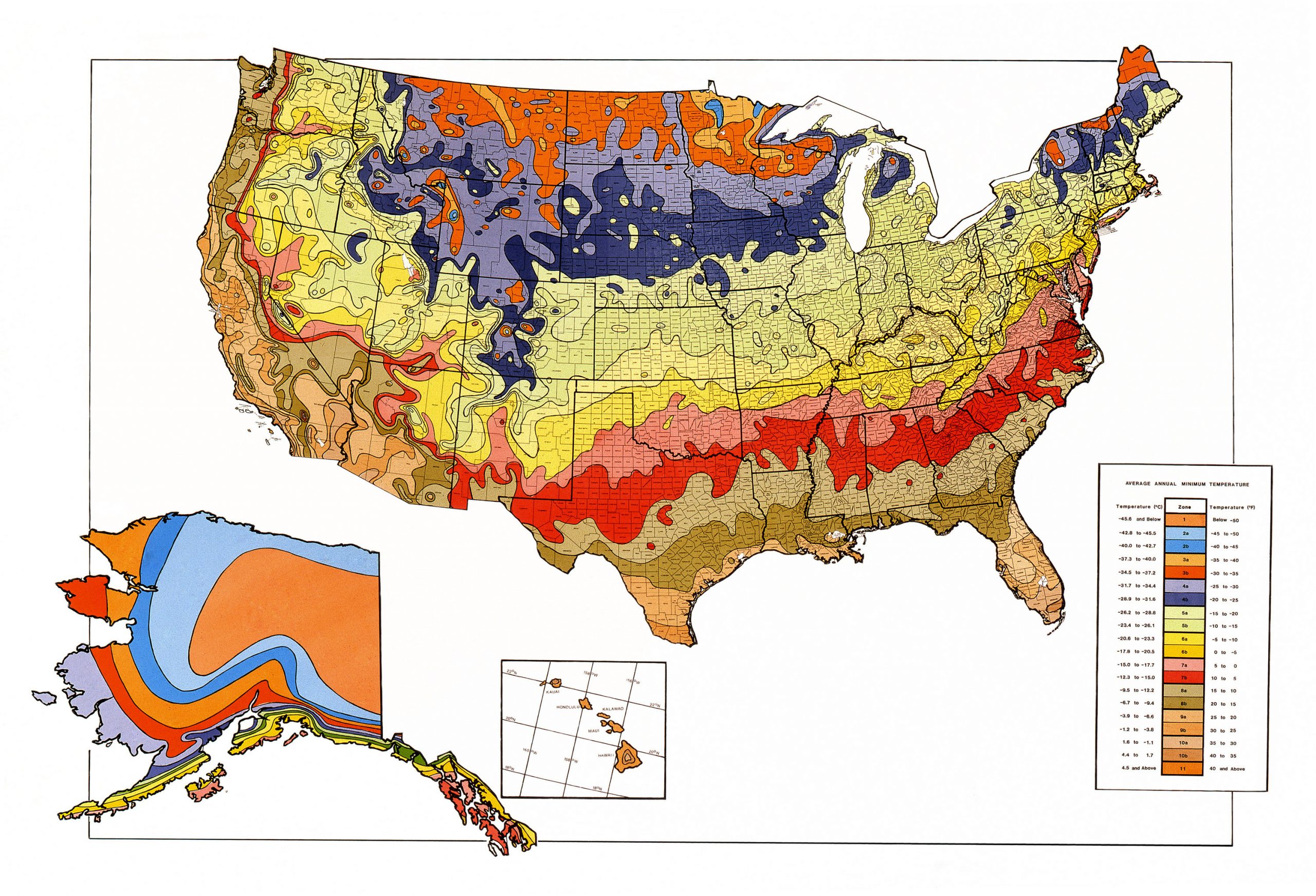

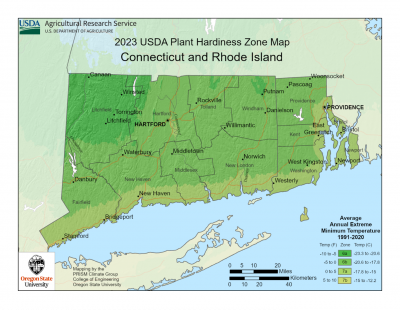

Options for growing camellias in Connecticut depend on what part of the state you live in. Thanks to breeding efforts of Dr. William Ackerman (retired USDA plant breeder) and Dr Clifford Parks (Univ of NC botanist) varieties of camellias hardy to zone 6 (-10 F) were developed. Depending on the variety and environmental conditions, camellias can bloom from fall to spring. Many of the most popular cold hardy, fall blooming cultivars belong to the Winter Series bred by Ackerman and include plants such as ‘Polar Ice’, Winter Charm’ and ‘Winter Rose’, the latter reaching only 2 to 3 feet high and wide making it a possibility for container culture.

Dr. Parks focused on cold hardy spring bloomers including the April series (C. japonica hybrids). Many grow from 5 to 10 feet tall and can be found at some local nurseries. Look for ‘April Rose’, ‘April Blush’, ‘April Remembered’ and ‘April Tryst’.

Keep in mind that our weather has been somewhat unpredictable so those in zone 6 might want to locate plants in a semi-shaded, protected location. Camellia flowers are just exquisite, resembling roses in colors ranging from white to pink to red. Some are picoteed, some are double and some are very fragrant. The dark green foliage holds up year-round.

Camellias, being broad-leaved evergreen shrubs, have similar requirements to rhododendrons. They do best in an acidic, well-drained soil amended with organic matter. It is often best to group them for effect and also for some protection from the elements. Plants are slow-growing and need adequate moisture but avoid planting them in poorly drained sites. Semi to full shade is preferable as the leaves may scorch in sunny, dry areas. A fertilizer for acid-loving plants can be applied in early spring as directed on the package. Pruning is rarely needed but could be done right after flowering.

I’ve never been fortunate to live in a warm enough location to plant camellias outdoors, but several cultivars are perfect as house plants if kept in a cool spot indoors. Two available from Logee’s in Danielson are ‘High Fragrance’ with delightfully scented light pink semi-double flowers and ‘Scentuous’ with fragrant, semi-double white blossoms. They have others blooming in their greenhouse.

Growing camellias in containers is a splendid way to get winter color, often along with fragrance. According to Logee’s co-owner and horticulturist, Bryron Martin, plants require an acid soil with a pH around 4.8 to 5.8. They can be grown in a camellia/azalea potting mix. Martin advises that young plants can be pinched back for fuller growth although that will delay flowering a bit. Keep in mind that some cultivars can get up to 6 feet in height so either select those that mature at a smaller size or be sure you have space to accommodate them.

Temperature is key to induce blooms. Ideally Martin recommends nighttime temperatures no higher than 59 F during the winter and preferably 30 – 40 F so an unheated room or sun porch is a great place for camellias. If nighttime temperatures are too high, the buds will drop. An east or west exposure will provide adequate light.

Fertilize camellias in the spring when active growth begins. Use a fertilizer for acid loving plants as directed. Commercial synthetic and organic camellia fertilizers are available. Some growers use a cottonseed meal/bloodmeal homemade blend. To supply adequate magnesium to plants, Martin recommends dissolving 1 tablespoon of Epsom salts in a gallon of water and applying this mixture twice a year.

For late fall through spring blossoms, indoors or out, camellias are attractive, evocative plants that perhaps more folks might consider cultivating. Those looking for a Valentine’s Day activity might consider the Camellia Festival at Planting Fields in Oyster Bay, NY. The Lyman estate in Waltham, MA also has a camellia greenhouse that is open to the public.

The UConn Home Garden Education Office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant January 18, 2026

Plan Early For A Great Growing Season

By Heather Zidack, UConn Home Garden Education Office

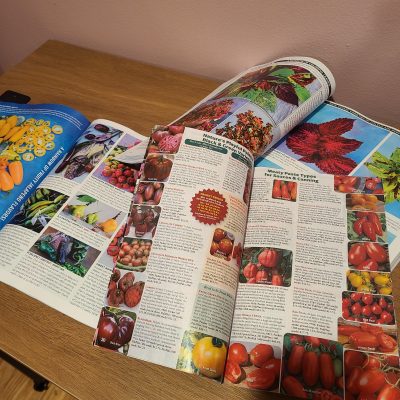

As you start to plan your next vegetable garden, you may reflect on the previous seasons to help you develop your seed selection, layout, and more. Gardening can already be a sustainable practice, but many want to be more intentional with reducing waste, improving efficiency, and promoting sustainability in their home. Your stages of garden planning should include considerations to ensure you are meeting these goals during the growing season.

The first way to improve your practices is to have an honest assessment of your strengths and weaknesses as a vegetable gardener. For example, through years of trial and error, I have finally admitted out loud that I am not skilled at keeping pepper seedlings warm enough to yield bountiful plants in the growing season. As a solution, I now buy my pepper plants from the garden center in the spring, while still using my setup to start other vegetables and flowers from seed. Using the garden center to help fill in gaps allows you to use that time, energy, and money for seed that has a track record of success. You might even have space to try something new!

Plan to save seed before your plants even start growing. Select seed varieties listed as “open pollinated” so that the offspring will come back true to seed in the following season. Plants that do not have this designation may not come back true to type and may lead to unfamiliar plants in the future!

Consider space as a commodity while you’re planning your garden. Think about the space that some plants require, and determine if that product is worth that space, time, and energy. If your row will yield half a dozen heads of cabbage from weeks of watering, weeding, and care, does that meet your gardening goal? Or do you have other goals in mind? Decisions like this early in the planning stages can help you make your garden more efficient, productive, and tailored to you.

Prevent waste by growing what you and your family will eat. Sometimes gardeners get caught up in the novelty. Purple cauliflower is exciting and worth the space if your family will eat the cauliflower. Avoid overplanting to keep your garden efficient and reduce waste. Does your family get sick of certain produce mid-season? That could be a clue that you're overplanting. When planning for the year ahead, ask yourself if your family has the capacity to eat or safely store whatever is harvested when it is ready. Plant yields are easily researched to help you determine how many plants you may need in your garden to meet your goals.

It can be difficult to consider cutting certain vegetables out of your garden for space or efficiency. However, this is where local agriculture can assist. Just like buying pepper starts from the garden center saves time and energy in the seedling space, buying local produce can help fill any gaps you may feel in your garden’s productivity. From a sustainability standpoint, buying local usually means less energy used in transportation, refrigeration and storage when compared to produce from outside our region.

Cost Share Agriculture (CSA) programs are an effective way to supplement your garden produce. These programs often work on a shareholder system, where purchasing a membership up front will guarantee a share of the farm’s harvest throughout the season usually on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. Connecticut has CSAs for produce, cut flowers, and even meat products. Many of them start signups well before the growing season begins, so keep an eye out! Visiting local farmers markets is another way to help supplement your garden produce, with less of a regular commitment. Some even provide forms of family entertainment, like music, during the summer.

As you plan your next garden, remember that sustainability starts with intentional choices and there is no “one size fits all” strategy. Carefully considering your strengths, weaknesses, and goals will help you promote a sustainable and efficient garden in the season to come.

The UConn Home Garden Education Office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant January 10, 2026

Five Soil Myths That Cost Home Gardeners Money

By Dr. Avishesh Neupane, UConn Soil Nutrient Analysis Lab

Every spring, I see the same scene in garden centers. Carts piled high with lime, fertilizer, gypsum, compost-in-a-bag, and something in a shiny package that promises instant results. When I chat with home gardeners, I often ask: How did you decide you needed all of that? Most of the time, the answer is, “I don’t really know. It looked helpful.” As someone who works with soil tests every day, I see the other side of that story. I see the lawn with three times more phosphorus than it needs. The vegetable bed that gets lime every year, even though the pH is already high.

A lot of this comes down to a few myths that are passed down by neighbors, family, and well-meaning advice on the internet. But they quietly drain gardeners’ wallets and sometimes weaken the very plants people are trying to help. Here are five of the most common myths, and what to do instead.

Myth 1: If my plants look okay, I don’t need a soil test.

Plants will try their best in less-than-ideal conditions. By the time plants show clear distress, the problem is often advanced. pH has drifted far from the ideal range. One nutrient is so high that it is starting to interfere with others. In the lab, I see plenty of samples from landscapes that “seem fine,” where the numbers tell a very different story. I also see the opposite. People are convinced their soil is terrible, but the test says they are in good shape and only need minor tweaks.

This myth costs money because skipping the test means guessing. Guessing leads to buying products you do not need and missing the changes that would help the most. A better approach is to test your soil every few years, or sooner if you are starting something new. A good test provides clear recommendations matched to what you are growing.

Myth 2: More fertilizer equals better plants.

People worry they are not fertilizing enough, so “a little extra” feels like good insurance. Extra nutrients do not automatically translate to extra health. Instead, excess fertilizer can burn roots and foliage, push lush but weak growth that attracts pests and disease, and wash into streams and lakes where it fuels algae blooms, harming the environment.

This myth costs money as you are paying for nutrients your plants cannot use. You may also pay later for disease control or to repair damaged turf and stressed garden beds. A better approach is to view soil test recommendations as a ceiling, not a suggestion to exceed.

Myth 3: You should lime your soil every year.

Many people learned that you “always lime the lawn in the fall.” As many native New England soils are naturally acidic, lime can be important in the right amount and in the right places. But I also see plenty of tests where pH is already in the upper 6s or above 7, and the lawn is still getting lime out of habit.

When pH gets too high for the plants, iron and other micronutrients become less available. Acid-loving plants like blueberries and rhododendrons struggle. This myth costs money twice. First, you pay for lime, then you may pay to fix the problems caused by a high pH. A better approach is to test soil pH and apply only when it is recommended.

Myth 4: Adding sand will fix heavy clay soil.

Clay dries slowly in spring, sticks to tools when wet, and can feel like a brick when dry. A bag of sand looks like an easy fix, but mixing a little sand into a lot of clay does not make loam. It often makes something closer to concrete. What truly helps clay is organic matter. Compost and well-rotted manure can loosen heavy soils, improve drainage, and support healthier soil structure and biology.

This myth costs money because you buy sand, haul it around, and see little improvement. For most home gardens, adding organic matter works much better.

Myth 5: Bagged topsoil or garden soil is always an upgrade.

Big bags and bulk deliveries of “topsoil,” “garden soil,” or “planting mix” can feel like a shortcut to perfect beds. Sometimes they are excellent, but at other times they are basically subsoil with a nicer name, which can cause problems like high salt levels, unbalanced nutrients, or a pH far from the target.

This myth costs money because poor-quality material means paying twice. Once to bring it in, and again to correct it. A better approach is to ask suppliers what is in the mix and how it is produced. And whenever possible, improve the soil you already have.

The Common Thread

The common thread in all five myths above is that we reach for products before we understand the soil. If you start with a test, you can skip lime when your pH is already in range, cut back on fertilizer where nutrients are high, and put your time and money into the changes that will actually move the needle. That is better for your plants, your budget, and the rivers and lakes downstream. Your garden does not need every product on the shelf. It just needs the right help at the right time.

The UConn Home & Garden Education office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant January 4, 2026

2025

Cranberries, A Symbol of Holiday Cheer

By Nick Goltz, UConn Plant Diagnostic Lab

Each holiday season, a wave of bright red cranberries appears on Instagram feeds, Pinterest boards, and tables across the nation in the form of sauces, desserts, drinks, and decorations. Beyond their seasonal fame however, these tart red berries play a major role in U.S. agriculture and culture.

Let’s start with some numbers. The USDA estimated the 2024 U.S. cranberry harvest at about 8.24 million barrels, roughly 824 million pounds of fruit. Here in the U.S., the cranberry king is Wisconsin, producing nearly 4.9 million barrels, around 60% of the national total. In second place is the historical cranberry producer, Massachusetts, with approximately 2.2 million barrels produced in 2024. The top agricultural crop in the state, Massachusetts’ cranberry crop alone is valued at $73.4 million, supporting over 6,400 jobs and generating $1.7 billion in annual economic activity. Cranberries are so important for Massachusetts, in fact, that they are the state fruit and cranberry red is the state color.

Cranberries, known scientifically as Vaccinium macrocarpon, are native to North America and are a close relative of blueberries. Compared with blueberries however, cranberry plants tend to be smaller, low to the ground and vine-like. The vines require acidic soil (pH 4.0–5.5), a reasonably cool growing season, and abundant fresh water. If these conditions can be emulated at home, cranberries can make an attractive edible ground cover. They perform well when planted alongside plants such as conifers and rhododendron, provided they are given plenty of water and appropriate fertilizer for acid-loving plants.

For commercial production, cranberries thrive in uniquely engineered wetland environments - bogs built atop beds of sand, peat, gravel, and clay. The annual commercial production cycle of cranberries begins with winter flooding, which forms protective ice that shields the vines and prepares the surface for sanding, which stimulates spring growth. As temperatures rise in spring, bogs are drained, and bees pollinate the blossoms. Summer is devoted to irrigation and monitoring, followed by harvest from mid-September through early November, before the cycle repeats with winter flooding and freezing.

Cranberry growers will typically harvest their crop one of two ways: through wet harvesting or dry harvesting. Wet harvesting describes the process where bogs are flooded to allow berries to float to the surface before being netted and loaded into equipment for cleaning and processing. This harvesting technique is the most popular, but requires proper equipment and careful planning. Dry harvesting, the process of using mechanical pickers that comb berries into conveyers, is an approach primarily used for fresh markets. More fruit are left on the vine with this approach, but the collected berries for fresh market can be sold at high prices and dry harvesting allows growers without the means to flood and drain their bogs on a schedule to grow cranberries.

Cranberries are deeply embedded in holiday traditions, thanks to their seasonal harvest, festive red color, and historical use. For more than 12,000 years, they’ve been utilized by Indigenous communities, especially the Wampanoag People, for food, medicine, dye, and winter preservation. The cranberries collected by hand in the bogs of southern Massachusetts were both eaten fresh and dried for shelf stability, then eaten as-is later in the winter or mixed with dried meats and fat to make pemmican, a hearty winter staple.

European settlers in New England quickly adopted the appreciation of cranberries, integrating them into winter celebrations. By the 18th and 19th centuries, cranberry sauces, relishes, and baked goods were staples of Christmas feasts. Their vibrant red hue also made them popular in holiday crafts such as cranberry-popcorn garlands or wreath embellishments.

U.S. cranberries reach peak consumption during the holidays. Though 95% of cranberries are processed into juice, sauce, or dried fruit, fresh cranberries remain a holiday staple, used in everything from stuffing and pies to cocktails and décor. Around 400 million pounds are eaten annually, with an estimated 20% consumed during Thanksgiving week, about 80 million pounds. With per-capita annual consumption averaging 2.3 pounds, mostly in juice or processed form, cranberries rank second among berries consumed in the U.S. after strawberries!

Cranberries exemplify a convergence of historical tradition and the advances of modern agricultural practices. They support regional economies, sustain traditional farming techniques, and bring seasonal joy to millions. As you gather with loved ones this holiday season, enjoy an extra serving of these tart crimson berries and remember that food isn’t just sustenance, it’s heritage, celebration, and connection.

The UConn Home Garden Education Office supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant December 27, 2025

Gifts for the Gardener on Your List

By Heather Zidack, UConn Home Garden Education Office

If you have a gardener in your life, last minute holiday shopping can be tough. Each year, we provide a list of suggestions that might help you as you’re shopping. For 2025, we are considering gardener comfort and adaptability.

Gardening Gloves

While it seems like a trivial gift and your gardener may already have a good pair, gardening gloves are a great gift! It’s always nice to have an extra pair in case your hands get wet working in muddy soil, or if you manage to lose them. Our gloves wear over time, and can thin, stretch, and decline in quality as seasons change. While any pair may be helpful as a backup pair, you might get bonus points for finding your gardener’s favorite brand or style. These are readily available in hardware stores or year-round garden centers.

UV Protective Clothing

With the improvement of UV protective textiles, gardeners can find them in all sorts of forms. UV shirts, gloves/sleeves, and even hats are available to help your gardener stay protected from the sun. This is great for anyone who loves being outdoors, but especially those who may have extra sensitivities to sunlight. While not a direct substitute for sunscreen, they can help provide a little extra protection. I find that these often are best found online, though I have seen individual items at independent garden centers, sporting stores, and gift shops throughout the state.

Cooling Towels

Athletic cooling towels are meant to help keep you cool. Soak them in cool water, wring out the excess and wear as a scarf or drape over your shoulders. The evaporative cooling from the towel helps you stay cool even during the warmest summer days. While they’re usually found with the sports gear, your gardener will love them, too!

Waterproof Shoes

Nobody likes wet feet, especially in the garden. Help the gardener you love stay dry by gifting them with a pair of waterproof shoes! These come in many forms such as rubber rain boots, rubber clogs, or even waterproof sneakers. They can be found at sporting goods stores, shoe stores, or online.

Shop Smart

There are many gifts beyond these recommendations that may suit the gardener in your life. As we approach the last-minute shopping season, keep these tips in mind to help you find the perfect gift.

Look carefully at the label of any seed mixes, seed bombs, or other plantable gifts, especially if you are intending to gift native seeds. Many of these mixes sold across the country may provide plants native to North America, but not necessarily native to our region. The label provides a percentage breakdown of every species of seed included. Cross reference to ensure that they are native to our region.

Purchase durable tools and equipment over novelty items. Give your gardener gifts that they will be able to use for years to come. While gloves with claws to help you dig are fun and unique, a good trowel will stay part of your gardener’s arsenal for many years.

Consider your gardener’s interests to help guide your gifting. If your loved one plants more flowers than vegetables, a garden hod might not be the right fit for them. If they hate weeding, a gift to make the chore easier might be a great fit! Think about the ways the person you’re gifting likes to spend time in their garden and tailor your gift to them.

Don’t rule out experiential gifts just because it’s winter. Gardeners who wish to continue to learn and spend time with like-minded green thumbs may enjoy a workshop, class, or conference. Many regional garden shows (including the CT Flower & Garden Show) take place during the winter. Local garden clubs, libraries, or garden centers may also offer educational workshops that you could purchase tickets for in advance.

Shop smart. While we can’t recommend any brands or specific places to shop, use your smart consumer skills when looking for these or any other gifts this season. Reading reviews, using trusted retailers, and balancing quality with price will help you verify that these gifts will impress.

If you’re shopping last minute for that gardener in your life, remember that it doesn’t have to be stressful! Keep comfort, adaptability, and their unique interests in mind for a gift that’s sure to please!

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant December 20, 2025

Seasons Greetings

By Dr. Matthew Lisy, UConn Adjunct Faculty

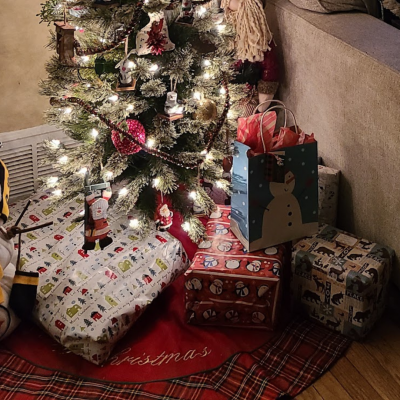

It is hard to believe it is that magical time of year again. Thoughts turn to how we are going to celebrate the holidays. This would, of course, include decorating our living spaces. Fortunately for plant people, there are no shortage of choices for the season. Plants also make wonderful gifts to take to a holiday gathering. After all, they bring nothing but joy and cheer.

The first holiday plant that comes to mind is the poinsettia. Although native to Mexico, they seem to have found their way into every corner of the country. It is not actually flowers that are the stars of the show, but the colored leaves. What was once a beautiful red has been selectively bred for some absolutely amazing colors. My all-time favorites include a newer snow-white colored one, yellow, and the orange varieties. If two-tone leaves are preferred, there are neat red with pink centers and white with pink centers – both of which look absolutely stunning. A new one for this year has snow white leaves with a slight pink blush at the center. Of course it does not end there! There are varieties like “Jingle Bells” which looks like the red has white paint splattered all over it, which makes it a real conversation piece. The “Christmas rose” comes in many colors now and has the leaves swirled into a rose shape.

The poinsettias are beautiful, but they take a little bit of TLC to get them to stay that way. They should only be watered when they are dry to the touch on the surface. Let them dry too long, and they drop leaves. Cold drafts will produce the same result. If water is splashed on the leaves, the spots will discolor and dry, ruining the look. These plants are best watered from the bottom by filling the tray they are sitting in with water and letting the soil and roots wick it up. Poinsettias tend to fall from grace after the holiday season, and therefore are treated as a temporary decoration.

There are a number of other plants that will make just as nice of a display. The first is the Christmas cactus. They bloom profusely this time of year. They also make a great houseplant if they are allowed to dry out between waterings. To get them to rebloom the following year, put them in a room that is only illuminated by natural light – mother nature will take care of the rest (they need a critical period of darkness to flower). These plants can be so long lived that they can become family heirlooms.

Some lesser-known plants include the frosty fern, which is not a fern at all, but a Selaginella (Spikemoss). Although some species can tolerate extreme desiccation, the species sold during the December holiday season cannot. These are great for people who love to over water because if they dry out at all, they will wither and die. They actually prefer to be in moist, soggy soil but not submerged. Cyclamen are nice looking plants with the flowers held above the leaves. These are somewhat long lasting, but tend to go dormant. They seem to be hard for most people to keep long term. Kalanchoe plants have beautiful flowers of all different colors, but these are also a challenge to keep as a long-term houseplant. Amaryllis bulbs can be beautiful when blooming, and after a dormant season may rebloom the following year. These are easy to keep provided the watering is done only while growing and not while dormant or dying back.

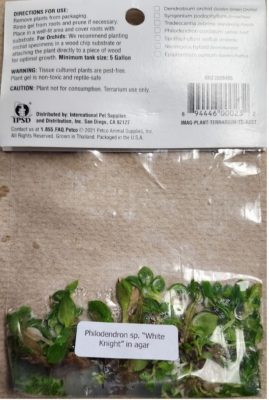

I do not know if it is the marketing or the colors of holiday plants that make them so popular, but do not forget about traditional houseplants for gifts. Some nice philodendrons, spider plants, pothos, or snake plants certainly make wonderful additions to any home. There are so many beautiful new varieties coming to the market all the time. No matter what plant species is chosen, plants tend to put a smile on the face of the receiver. In my opinion, there is no greater gift. If the choices are too many, then why not get a gift certificate for a local independently owned nursery or greenhouse? Happy holidays!!!

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant December 13, 2025

Barn Cupolas And What They Do

By Pamm Cooper, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

Cupolas are small structures built over a hole in the roof centerline to provide light, ventilation, a nice view or perhaps some decoration to the overall structure. While found on many kinds of buildings including the International Space Station, the main purpose of barn cupolas is functional over form. With the advent of tighter barn construction to keep livestock warm during the winter, moisture buildup became a problem. The cupola became a necessary addition to barns to help reduce this moisture buildup and to allow fresh air to enter the barn.

While used in the Middle East and eventually in Europe, these structures were more decorative than functional. They were eventually used less as domes became more popular. In the United States, cupolas were introduced in the late 1700s by settlers from Europe and used as barns increased in size and allowed for more hay storage and livestock housing. Tighter construction by means of siding and better roofing became the norm in the mid 1860s, and this resulted in ventilation issues as moisture levels increased.

The larger amounts of hay could build up heat and occasionally spontaneous combustion occurs if fresh air is not provided. Both the hay and the barn could be destroyed. Tighter barns also meant more moisture from both the breathing of the cows and from a constant deposit of urine and manure. Fresh air and the removal of moisture was needed for the health of livestock and to prevent mold developing on and ruining stored hay.

The solution was a nifty piece of architecture called a cupola. Farmers started installing cupolas as a means to draw out hot, moist air and stale gases from manure via louvered slats on all four sides. Fresh air could also enter while rain and snow were mostly kept from entering the roof as these louvers were downward facing. The health of livestock kept in close quarters in cold weather improved, and mold development on stored hay was reduced through this ventilation. Additionally, livestock kept warmer in the cold months required less food, so hay lasted longer and in good condition.

The spacing, size, and number of cupolas needed depended upon the linear footage of roof centerlines. The number of livestock and amount of hay storage were also considered. This is why some barns have many of these structures, while other barns may only have one or two. Barns with open sides have no need for cupolas.

While the primary function of cupolas has been to provide ventilation for haylofts and livestock areas, there are many styles of cupolas that also incorporate various decorative designs. On Hanks Hill Road in Mansfield, there are two barns on two different properties near each other that have the exact same unique design, which is rather fancy while still being functional. I suspect the same person designed and built both as they are almost identical in decorative woodwork and unusual peaked roof lines. I have not found other cupolas with such intricate woodwork and wonderful design features.

Historic barns often have fixed or awning windows that either don’t open or that are hinged on the top or bottom and open only slightly. Some cupolas are topped with a weathervane or a finial. Farmers took great pride in their barns. They could be a large investment, so it’s understandable that many put elaborate cupolas on their barns to make a statement about their pride and prosperity. As you drive around farm country, perhaps now you will notice some interesting cupolas that have been there all along.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension Center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant December 6, 2025

Highlighting Connecticut’s Winter Cheer: Common Witch Hazel

By Holly McNamara, UConn Plant Diagnostic Lab

Connecticut’s native species of Witch Hazel, Hamamelis virginiana, is a remarkably unique woody ornamental that can be found as a large shrub or small tree. It comes to the rescue this time of year as the leaves continue to drop and our surroundings become starved of color. Its foliage in autumn is a showstopping yellow.

Hamamelis virginiana can grow between 10 and 20 feet tall and is often nearly just as wide as it is tall. In ideal conditions, some can even grow as large as 30 feet tall. It has a loose and somewhat open, irregular rounded shape and is very attractive in landscaping when used as hedge rows, woodland edge planting, or along a pond or river. It’s the last plant to come into bloom each year in the Northeast, blooming from October to December. The bloom coincides with its flashy fall foliage, making it one of the most eye-catching specimens of the winter landscape.

The blooms are bright yellow with spidery, ribbon-like petals and have a pleasant citrusy fragrance. They are clustered tightly around the branches, and the petals curl up protectively during cold spells. A few cut branches in a vase will be sure to perfume and brighten up your home during the dreary winter months. Its late flowers attract certain species of flies, bees, gnats, and cold-tolerant moths. These insects are a food source for native songbirds such as kinglets, chickadees, and titmice.

The medicinal qualities of the Common Witch Hazel are world renowned and have been utilized for centuries. Its anti-inflammatory properties serve as a soothing remedy for bruises, itches, sunburns, acne, and small wounds. In fact, Common Witch Hazel extract is one of the only medicinal plants approved by the FDA as a nonprescription drug. Always consult with a medical professional before incorporating the use of medicinal plants. It's worth noting that there have been several Witch Hazel processing plants in Connecticut, starting in the 19th Century. To this day, most of the world’s Witch Hazel extracts are still produced in East Hampton, Connecticut.

Consider planting a Common Witch Hazel or two in your yard, mixed with hollies, viburnums, and dogwoods for some late-season cheer. Common Witch Hazel will grow in a variety of conditions, from moist to dry, and shaded to sunny. Flowers are most abundant when planted in full sun. It prefers acidic, nutrient-rich, well-draining soil. It’s quite hardy, growing in zones 4 through 8, and has very little trouble with pests or diseases. After establishment, they are virtually care-free. The only maintenance of note is periodic pruning to remove suckers if a controlled shape is desired.

Although it is a slow growing plant, it is worth the wait when it bursts into bloom. With so much going for it, this is a plant that deserves greater consideration for use in ornamental landscapes and yards.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant November 29, 2025

Road Salt and Your Soil

By Dr. Avishesh Neupane, UConn Soil Nutrient Analysis Lab

When I was a graduate student from Nepal living in New Haven from 2012 to 2014, I kept noticing the same winter aftereffect across town. Along busy streets, the first foot of lawn by the pavement turned yellow and matted, and the road-facing sides of yews and hollies burned while the yard sides looked fine. Coming from a place that does not spread salt each winter, it felt backward. We made the road safer, but the plants and soil paid the price. At UConn’s Soil Nutrient Analysis Lab, we hear versions of this every spring. People send soil from a strip along the road or from a bed near the driveway and say that spot never greens up like the rest.

You have also likely noticed the symptoms. Fine particles form a crust on the soil surface where water evaporates. Turf browns right at the pavement edge. Buds on the roadside of a shrub fail to break. Evergreens brown on the street side when traffic spray carries salty water, while the interior needles stay green. Vegetable beds that sit too close to plow piles can exhibit poor emergence, tip burn, or slow growth, even when the rest of the garden appears fine.

What road salt does to soil

Sodium chloride (rock salt) is the most widely used deicer. Once it dissolves, it separates into sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻). Chloride is highly mobile. It moves with meltwater, so in a wet spring, it can leach through the soil and, where conditions allow, reach groundwater, affecting well water quality.

Sodium changes how soil behaves. In healthy soil, calcium and magnesium sit on exchange sites; repeated sodium inputs displace them, sealing the surface, reducing infiltration, and making the soil feel tighter right where plants already struggle. Sodium also competes with potassium uptake, so salt-burned spots can look nutrient-deficient even when tests show adequate levels.

Alternatives to sodium chloride are often less harsh but cost more. Magnesium chloride and calcium chloride melt at lower temperatures but still add chloride and can injure plants and corrode concrete and metal. Calcium magnesium acetate (CMA) is chloride-free and generally gentler, yet it’s pricier and harder to find.

Lab testing and management options

If you inform the lab that the sample is from a salt-affected area (such as a roadside, plow pile, or splash zone), they will interpret the numbers with that history in mind and, if necessary, use the appropriate salinity method for your sample.

- Soil pH and texture (and organic matter). Sandy roadside fill flushes salts quickly but is more susceptible to damage due to its low buffering capacity. Heavier soils with more organic matter hold up better but can crust at the surface after repeated salting. For optimal plant health and reduced salt uptake, aim for a pH of approximately 6.5–7.0; your report will include a lime rate if your pH is below this range.

- Soluble salts / electrical conductivity (EC). EC shows how salty the root zone was when you sampled. It is most informative right after winter or snowmelt, when salts are near the surface. For mineral soils, labs typically measure EC from a simple soil–water extract.

Start with prevention. Before winter, top-dress the first 1–2 feet along the road with a thin layer of compost to improve structure and exchange capacity. Keep that strip covered, overseed thin turf, or use a salt-tolerant edge, and ask the plow operator to place piles where meltwater drains to the street or to vegetation that isn’t over your well line. Where meltwater goes matters as much as how much salt you use.

After winter, fix what the season left behind. If the roadside sample shows elevated EC, lightly loosen any compacted or crusted soil so that water can infiltrate. Then, leach the area with two or three deep soakings a few days apart to push salts below the main root zone. If a hedge or shrub burns on the roadside year after year, consider moving it back or replacing the front row with more salt-tolerant plants.

For chronic hotspots, shift from one-time flushing to long-term protection: use less deicer, keep piles away from beds and wells, maintain dense groundcover in the first foot along pavement, and in harsh exposures, consider stone mulch plus seasonal compost topdressing to help the soil rebound.

If your well water tastes salty, check the state’s road-salt guidance and contact your town. When the damage is limited to curb strips or driveway beds, soil testing and better winter practices usually solve it.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant November 23, 2025

Winterize your Garden Gear Before It’s Too Late!

By Heather Zidack, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

It’s already November! It doesn’t seem like that long ago when we were giving advice about seeding lawns and watering in new fall plantings. Now that the time has changed, the days feel shorter, and the nights are getting colder, it’s important to remember to take the time to properly store your garden equipment and accessories before locking up the shed for the season.

Freezing temperatures are on the way fast. Drain and roll up any hoses to remove tripping hazards from the landscape. Store them inside a garage or shed to keep them out of the elements and lengthen their lifespan of use in the garden. Make sure that your outdoor water systems are properly winterized. Whether that means flushing your irrigation system, or simply shutting off your outside water, don’t forget this important step to protect your pipes! Once lines are turned off, open external valves to relieve any remaining pressure.

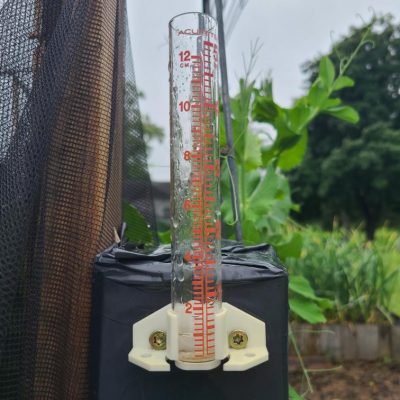

Water can not only wreak havoc on pipes but many garden accessories, too. A glass rain gauge left outside can and will freeze and shatter outdoors. Ceramics like pottery and bird baths are susceptible to cracking, so store them either in the shed or upside down in a sheltered area. Stash your garden gnomes, garden flags and solar pathway lights to protect them from fading and damage. Brittle cold, freezing water, and a careless throw of the snow shovel could spell disaster for garden décor left out in the open.

Inside the shed, take a quick inventory. Leftover seed or bagged mulch could be rodent attractants. Seeds should be stored in areas safe from extreme temperatures to preserve germination rates. Bird seed should be stored in animal proof containers. Chemical products like pesticides and fertilizers may be adversely affected by temperature fluctuations and freezing. They could also make a real mess if a water-based or pressurized solution were to burst. Products leftover from the growing season should be evaluated and moved into a space safe from freezing temperatures. Product labels or manufacturers will have storage and disposal information to help you make the best decision about what to do with your garden chemicals at the end of the season.

Winter will be a great time to thoroughly clean, repair, and sharpen tools. Store them somewhere that is easy to get to later so you can make sure your tools are fresh for the new season! If you have to do the seasonal shed shuffle, this is also a great time to rotate the lawn mower and snow thrower to prepare for the first storms of the season.

Speaking of your gas-powered equipment, check your owner’s manuals for winterizing recommendations and instructions to help maintain the life and quality of your equipment. You may need specific maintenance before long term storage. Contact a professional for any maintenance tasks that you do not feel confident performing on your own.

If you’re running out of space in the shed and garage, consider covering lawn furniture with UV and mildew resistant covers. Take down awning covers and temporary structures. I, myself, have fallen victim to the false sense of security of a mild winter, only to be devastated by the collapse of my garden tent in the first, albeit belated, heavy snow.

While all of this seems like common sense, the mad dash from here to the holidays will have many of us pulled in different directions. Our equipment, tools, and garden infrastructure are some of the biggest investments we put into our gardens. Hopefully this short checklist will help you knock out those last few chores that come with maintaining a four season New England garden.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant November 8, 2025

Chestnuts: A Tasty Thanksgiving Treat

By Dawn Pettinelli, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

With Thanksgiving approaching, many of us will be sitting down to hearty feasts with family and friends. Time-tested recipes on worn index cards or heavily thumbed cookbooks are combed through/uncovered. Many of us gardeners pick a few new plants for our gardens each year, so why not try a new plant on the dinner table? Chestnuts were reputedly served at the first Thanksgiving and thanks to dedicated breeding programs may be available locally today.

It’s hard to imagine that a little over 125 years ago there were probably 4 billion American chestnuts (Castanea dentata) spread out from southern Maine to northern Georgia. They were an important food source for both indigenous people as well as wildlife. Early European settlers found their rot resistant wood useful for many building purposes.

Unfortunately, a disease (Cryphonectria parasitica), known as chestnut blight, was unintentionally introduced in 1876 on imported Japanese chestnuts (C. crenata). These were sold via mail order throughout the eastern U.S., and our native American chestnuts soon became infected. This fungus spreads by windblown spores. Signs of infection include a reddish-orange ‘rash’ on the affected bark and as it reproduces, an orangey substance oozes from pores in the bark. Cankers form and eventually the plant can no longer internally transport water and nutrients. Chestnut blight kills the parent tree but not the roots so even to this day, you are able to find sprouts growing from chestnut roots. As the sprouts develop, they too will be killed back by the blight so while the tree is kept alive, American chestnuts are considered functionally extinct, but all is not lost.

Fortunately, both researchers and chestnut lovers have been working pretty much for the past 100 years on developing varieties resistant to chestnut blight. Breeding work has been done in many locations but the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station began their program in the early 1900s and it is the only program that has continued uninterrupted to this day. Presently this CAES program is led by Forest Pathologist and Ecologist, Dr. Susanna Kerio.

Various chestnut species including American, Chinese Japanese and European have been crossed, backcrossed, planted, evaluated, culled and selected by researchers and enthusiasts all over the eastern U.S. As one can imagine, it takes more time to evaluate a tree’s characteristics than say, an annual plant like a tomato.

Organizations like The American Chestnut Foundation started in 1982 have been championing the search. According to Deni Ranguelova, the New England Regional Science Coordinator, the goal is to develop blight resistant chestnuts and restore this magnificent tree to its native range. Members of this organization have the opportunity to obtain straight species or hybrid seed to try their hand at growing chestnuts and add observations to the chestnut knowledge base.

Why all this work on chestnuts? Well for one, they are deliciously mild and sweet. They are low in calories and high in fiber. Chestnuts are a good source of potassium and other nutrients. Eat them freshly roasted (just like in the song!), in holiday stuffings, soups, in main dishes and glazed. To cook them, they do need to be scored whether oven roasted, boiled, steamed or microwaved to keep them from bursting. Lots of instructions, recipes and videos can be found online.

Second, plants are productive. In fact, it was estimated that before their demise that a mature American chestnut may be able to produce 6000 nuts! They can serve as a food source to both people and wildlife as researchers and enthusiasts create blight resistant strains to plant in our natural areas or in commercial orchards.

Aside from being a member of The American Chestnut Foundation and obtaining seed, one can order chestnut seedlings from several online nurseries. Keep in mind that chestnuts do best in a sunny area with well-drained soil. Root rots can occur in poorly drained areas. Plants are being bred to be straight and tall for timber, or shorter and wider for nut production. Make sure you have enough space for a mature chestnut tree, or most likely 2 trees as chestnuts need another plant for cross pollination.

Even if a chestnut tree is not in your future, do try some chestnut dishes at your Thanksgiving table. They may start a new tradition.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant November 15, 2025

You Are the Sunshine of My Life

By Dr. Matthew Lisy, UConn Adjunct Faculty

This old song seemed like the perfect title for talking about artificial lights for houseplants. Even if there are windows in a room, the amount of light is very low. Fortunately, there are relatively cheap LED options available. Light is made up of the different colors, or wavelengths, of the visible spectrum – Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet. A plant’s pigments capture light energy and use it to make food. Chlorophyll production peaks in the red and blue spectrums, but accessory pigments help plants capture additional wavelengths of light. As such, there are optimal wavelengths of light that will better support plant growth. This is known as Photosynthetically Active Radiation, or PAR. We measure PAR by using the Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density, or PPFD. This measures the amount of photons of light in the correct range hitting a specific area, and is measured in micromoles per square meter per second (µmol/m2/s). A PAR meter is an expensive way to measure how much usable light is available for your plants.

LED specialty lamps that have a good spectral output (PAR) are easily acquired. I would caution the buyer to read the reviews to help judge the quality. Good lights will generally include some description of PAR and/or PPFD. Light quickly diminishes with distance, as it essentially becomes less concentrated. Look in the product information for how close the plant should be to the light for maximum effectiveness. Generally, keep the plant 12-18 inches away from the light source. If it is too close, or the light is too bright, plants can be burned, drop leaves, or become spotted. A cheaper option is to use existing light fixtures and replace the bulbs with either full spectrum or plant grow bulbs. The ideal plant grow bulbs look pink, as they have red and blue LEDs. Full spectrum bulbs tend to have a better mix of wavelengths to make the light appear more natural to us, but still have good PAR. CRI, or Color Rendering Index is a measure of a light’s ability to accurately show colors compared to natural light. The closer to 100, the better the light’s appearance.

We can also judge a bulb by “color temperature” reported with a Kelvin number. For example, a 2700K bulb is commonly referred to as a warm white. This is reminiscent of the light given off by a traditional incandescent bulb, and shows heavier output in the red end of the spectrum. A 6000K bulb would be called a “daylight” bulb, and has a heavier output in the blue end of the spectrum.

Many people confuse quality of light with brightness, which is measured in lumens. Light can be very bright, but of poor quality. Too bright, and it may burn the plants. Also, buying a light that throws out a lot of green light does not do much, even if it has a high output (lumens). Lastly, Watts are used as a measure of energy consumption. While it is true that higher wattage may mean a greater output of light energy, the efficiency of LEDs means that a lot less watts are needed to put out the same number of lumens as compared to an incandescent bulb.

So, then, this begs the question: What light is best for growing plants? To answer, I am going to assume that the plants are going to be displayed in the living area and viewed by people regularly. In this case, I would try and find a 5000K bulb with a CRI close 97 or 98, and a PPFD rating that matched the requirement of my plants for the given distance from the light fixture.

The following is a quick list of what is useful and what is not useful as a metric for plant growth:

PAR - Photosynthetically Active Radiation. It is the ideal measurement for plant growth.

PPFD - Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density. It is a useful metric to judge output at a particular distance from the fixture.

Kelvin - Kelvin refers to “color temperature” – lower number more red (ex. 2700), higher number more blue (ex 6500). It is not detailed enough as a metric for plant growth.

CRI - Color Rendering Index. It is useful for how true-to-life the plants will look.

Lumens - A unit to measure brightness. It is not particularly useful as a metric for plant growth.

Watts - How much energy is used to run the bulb/fixture. It’s not useful as a metric for plant growth, but lower wattage costs less to run equipment.

Warm vs Cool - Warm indicates the red end of the spectrum while cool indicates the blue end of the spectrum. See Kelvin. It is not detailed enough as a metric for plant growth.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant November 1, 2025

Don’t Let Dry Soil Follow Your Plants Into Winter!

By Holly McNamara, UConn Plant Diagnostic Lab

This year, Connecticut’s notably dry summer conditions have continued into fall. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, all counties are abnormally dry for this time of year, and some are even considered to be in a moderate drought. Thus, many trees, shrubs, and perennials are heading into winter low on moisture. These conditions combined with the dry air, low precipitation, and fluctuating temperatures characteristic of Connecticut winters can lead to plant damage if no supplemental water is provided. Many of your plants will benefit from a deep final soak before the ground freezes.

Fall drought stress often doesn’t show up until spring, or even the following summer.Affected plants may appear perfectly normal and resume growth in the spring, using stored food energy. Plants may be weakened or die in late spring or summer when temperatures rise. Browning evergreens, delayed leaf-out, and sudden dieback are common signs of plants that went into winter too dry.

Moist soil is so important in the fall and winter months because it provides insulation to the roots. It may seem counter-intuitive, but properly hydrated soil does a much better job at protecting roots from freezing temperatures than dry soil. Root damage occurs for this reason when plants do not receive enough late-season moisture.

Woody plants with shallow root systems require the most supplemental water during extended dry periods in the fall and winter. Trees in this category include maples, birches, willows, and dogwoods. This category also includes perennials, and shrubs like hydrangeas, boxwoods, and azaleas. These plants benefit from mulch to further conserve soil moisture and buffer the roots from temperature swings. Apply mulch about 2 to 4 inches away from the trunk all the way to the outermost reach of its branches in a doughnut shape.

Evergreens also benefit from fall and winter watering because they do not go dormant in the winter. Evergreens of any age are still actively respiring during the coldest months of the year and will continuously lose water through their needles. If they go into the winter with dry soil, they are more likely to have a difficult spring recovery. This is especially true for those in open or windy areas.

Only water when daytime temperatures are above 40°F, ideally in the late morning or early afternoon so the water can soak in before possible freezing at night. Feel the soil at a depth of 4 to 6 inches to ensure that supplemental water is necessary. Soil should be consistently moist, but not oversaturated or muddy. Stop supplemental watering after the ground freezes because plants cannot absorb water through frozen soil. To water, use a soaker hose to provide a slow stream of water that can penetrate deeper into the soil with limited runoff. If your hose is already stored away for the winter, and your tree or shrub is small, consider drilling a 1/8-inch hole at the bottom of a 5-gallon bucket and filling that with water for a slow, steady stream. If dry weather continues into the winter and there’s little snow cover, additional watering once or twice a month may be needed until the soil hardens.

A final round of watering now can prevent root injury that won’t be visible until much later. Evergreens, deciduous trees, and other landscape plantings will head into winter stronger with a little extra attention this month. Giving the soil one last watering before it freezes is one of the simplest ways to protect your landscape from winter stress.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant October 25, 2025

Why is My Lilac Blooming in the Fall?

By Pamm Cooper, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

Spring-blooming woody plants like lilacs (especially the old, grafted varieties), ornamental cherries, forsythia, crabapples, azaleas and some magnolias set their flower buds for the following year in early summer shortly after flowering. Usually, flower buds are triggered to bloom by environmental conditions which normally occur after an extended fall and winter cold period, followed by longer days and warming temperatures in spring. It is not typical for these plants to have a second bloom in the fall, but environmental conditions sometimes trigger premature flowering in the fall. Some plants may have only a few flowers rebloom, while other plants may have more flowers open in the fall.

Some of the reasons for this out of season bloom are extended summer heat and drought conditions where supplemental water is lacking. Severe early defoliation, especially from certain fungal pathogens, can also contribute to reblooming. The past two springs have been very wet and diseases such as anthracnose and Pseudocercospora spp. leaf spot may have caused leaves to brown, shrivel and drop early. This stresses the shrub and contributes to out of sync rebloom if other conditions are right. Good sanitation practices such as cleaning up infected leaves will be helpful in reducing fungal infections the following year.

If a plant is healthy and relatively unstressed, the normal seasonal move to cooler weather triggers dormancy. Plants that are deciduous will drop leaves as daylight length and temperature both decrease. Next year’s leaf and flower buds will also remain in a dormant state. Flowering and leafing out will be triggered by increasing daylight and air temperatures the next spring.

If certain woody plants have been stressed during the growing season, however, the change to cooler weather followed by some warmer weather can trigger some of the flower buds to open prematurely. This false dormancy especially affects flower buds near the tops of old-style lilacs where it is sunnier and warmer. Ornamental cherries may show sporadic flowering all over the tree where there is a southern exposure.

While fall reblooming of ornamental trees and shrubs can lead to a disappointing floral display the following spring, it is not harmful to the plant. After a less showy spring bloom period, flower buds will be produced normally. If stressful conditions caused by environmental conditions, insect pests or fungal pathogens are minimal, then a second bloom in autumn is unlikely to occur. Gardeners and landscapers can only do so much, and while the weather is out of our control, making sure plants are maintained properly to avoid stress during the summer will go a long way in helping them remain as healthy as possible.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations.

This article was published in the Hartford Courant October 18, 2025

What’s changing with fertilizers in Connecticut, and how to shop smarter this fall?

By Dr. Avishesh Neupane, UConn Soil Nutrient Analysis Lab

If you shop for fertilizer in Connecticut this fall, you will see some labels missing from the shelves and more paperwork behind the ones that remain. The reason is new state rules targeting certain ingredients and how they are documented.

On October 1, 2024, Connecticut banned products made from biosolids or wastewater sludge that contain PFAS from being used or sold in the state as soil amendments. Biosolids are the treated solids left from wastewater treatment. Some products made from them were marketed for lawns and gardens in the past years. Connecticut’s new law closed that door to reduce PFAS in soils and runoff.

On October 1, 2024, Connecticut banned products made from biosolids or wastewater sludge that contain PFAS from being used or sold in the state as soil amendments. Biosolids are the treated solids left from wastewater treatment. Some products made from them were marketed for lawns and gardens in the past years. Connecticut’s new law closed that door to reduce PFAS in soils and runoff.

So what are PFAS and why the crackdown? Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a large class of “forever chemicals” added to products to resist water, grease, and stains. They do not break down easily and can build up in people, soil, and water. Health agencies have linked PFAS exposure to certain cancers, immune system effects, and developmental concerns, which is why Connecticut has been tightening rules to limit the entry of these chemicals into our environment.

Effective July 1, 2025, the legislature extended the PFAS biosolids restriction from soil amendments to fertilizers as well. The law also requires manufacturers and registrants to provide a certificate of compliance showing that any fertilizer or soil amendment that contains biosolids is free of PFAS. Products that do not meet the standard must be removed from Connecticut shelves.

What this means for your yard and vegetable beds is simple: expect fewer “biosolids-based” fertilizers on the market and expect clearer paperwork behind any products that remain. If you relied on those products for lawns or gardens, it is time to switch to other nutrient sources.

How can you read labels to avoid fertilizers and Soil amendments with PFAS?

- Check the ingredients panel. Look for words like “biosolids,” “sewage sludge,” “municipal waste,” or “residuals.” If you see those, consider a different product.

- Look for an analysis or ingredient list that spells out plant, animal, or mineral sources, such as feather meal, alfalfa meal, composted poultry manure, sulfate of potash, or rock-derived nutrients. These indicate non-biosolid ingredients.

- Ask your retailer. If a product contains biosolids, the maker must keep a certificate on file stating the product is compliant. Retailers should know whether a certificate exists for what they sell. If they cannot confirm, do not buy.

Safer sourcing ideas that are easy to find

- Start with a soil test. Match products and rates to what your soil actually needs. The UConn Soil Nutrient Analysis Laboratory provides routine tests with fertilizer and lime recommendations for home lawns and gardens.

- Yard-waste compost and leaf mulch made from leaves, grass clippings, and wood chips are reliable ways to add organic matter to the soil.

- Use animal-based fertilizers like composted poultry manure or feather meal, plant-based products like alfalfa meal, and mineral fertilizers like sulfate of potash and limestone.

- Biosolids are not allowed in certified organic production. “OMRI Listed” inputs follow the USDA National Organic Program, which prohibits sewage sludge. Choosing “OMRI Listed” products can be a practical way to avoid biosolids entirely.

A few quick FAQs

- Do I need to throw away the fertilizer I already own? Yes, but only if it contains PFAS or biosolids with PFAS. The new rules apply to the sale and use in the state. Contact your town’s household hazardous waste program for proper disposal guidance.

- Will PFAS show up on a routine soil nutrient test? Standard nutrient tests do not include PFAS. If you are concerned about legacy PFAS on a property that received biosolids, specialized testing is required. Your local Extension office can help you locate appropriate resources.

- What about compost from my town? Ask what goes into it. Compost made only from leaves, grass, wood, and animal waste is a safer choice for home gardens under the new rules.

Connecticut has removed PFAS-containing biosolids and fertilizer products from the garden marketplace. Expect clearer documentation from manufacturers and fewer sludge-based products on shelves. With a little label reading and a few ingredient swaps, you can keep building healthy soil while staying on the right side of the regulations.

The UConn Home & Garden Education Center supports UConn Extension’s mission by providing answers you can trust with research-based information and resources. For gardening questions, contact us toll-free at (877) 486-6271, visit our website at homegarden.cahnr.uconn.edu, or reach out to your local UConn Extension center at extension.uconn.edu/locations

This article was published in the Hartford Courant October 11, 2025

Got Garlic?

By Heather Zidack, UConn Home & Garden Education Center

Garlic belongs to the allium family, which includes onions, shallots, chives, and even some ornamental plants. People have strong feelings about garlic; they either love it or hate it. Whether you add it to your pantry of seasonings or not, there are tons of fantastic reasons to plant it in your garden.